I discovered Playboy the way most millennials discovered anything that mattered: through reality TV, in someone else's basement, the summer before I finally convinced my mother to get cable. Not the magazine itself—that would come later—but through three women who made being desired look like something you could control.

I'd spent that summer watching reality TV in my friend's basement—Rock of Love, Sunset Tan, Flavor of Love, Room Raiders, all reruns. I'd seen reality TV before, mostly Cheaters and Blind Date, but nothing I wanted to aspire to. Nothing that stuck. The Girls Next Door was different. There was something about watching Holly, Bridgette, and Kendra navigate the Playboy Mansion—Bridgette recreating costumes at Trashy Lingerie, throwing mini parties with Holly, custom theme-wrapping Kendra's 21st birthday gift. I wanted to fuck them and be them, a tension that's become central to my femme sexuality.

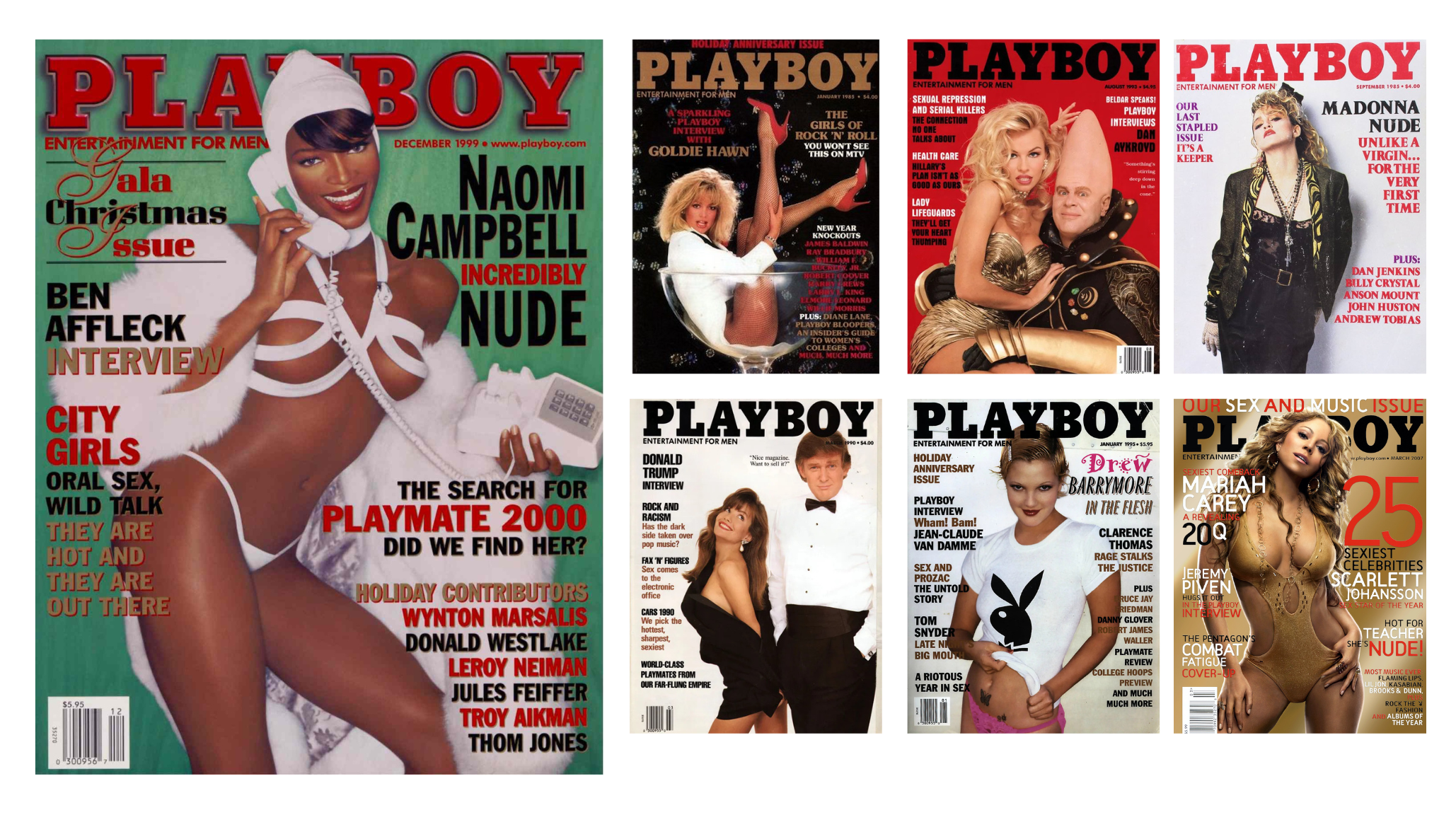

That show opened a pathway to Playboy itself. Before that, I'd found porn and adult magazines snooping through my uncle's belongings, but nothing that stuck with me. When I found Playboy, I was instantly imprinted. I was drawn by the element of escape, this visually stunning encapsulation of fantasy. It combined sex with culture in a way that felt approachable, digestible, beautiful. Look at any pictorial and there's a devotion to the craft. High budget, proper lighting, actual art direction. This wasn't smut; it was aspirational. That being said, I love smut too, different way though.

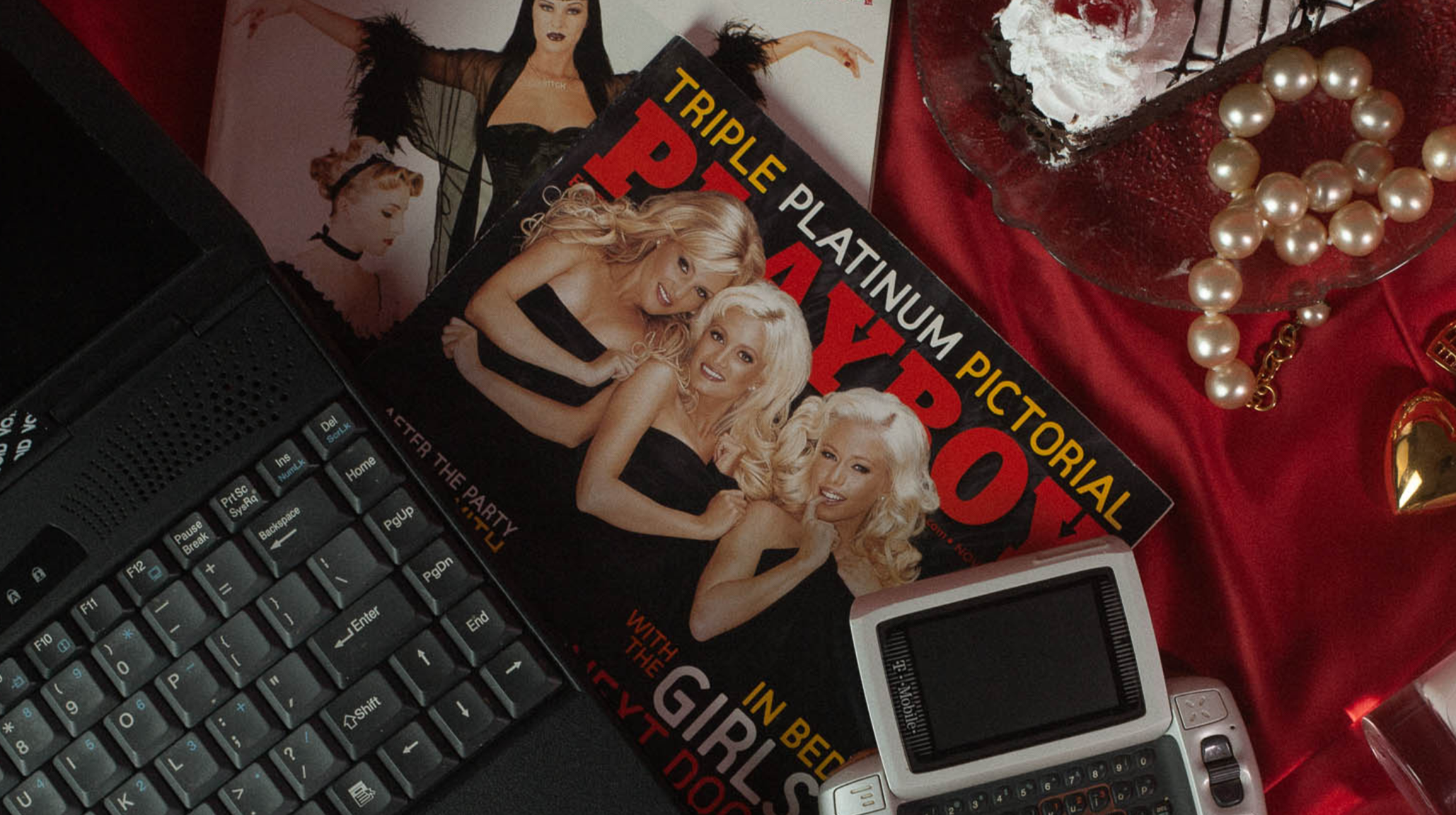

As I got older I started collecting Playboys. It was my first foray into erotica, a collection that has now outpaced my apartment and grown to include magazines, VHS tapes, books, coins from peep show booths, every medium you could imagine (and some you couldn't). But Playboy has always been special. For a long time, it was the cultural standard. In 2025? Not so much. But I think perhaps we could get back there, and if I'm being honest, we might need Playboy more than ever.

Yet even as I fell in love with what Playboy could be, I couldn't ignore what it had always been. The magazine launched in 1953 with Marilyn Monroe as its first centerfold—photos taken four years prior when she was struggling to make a car payment, used without her consent. From its inception, there was a disregard for women woven directly into Playboy's DNA.

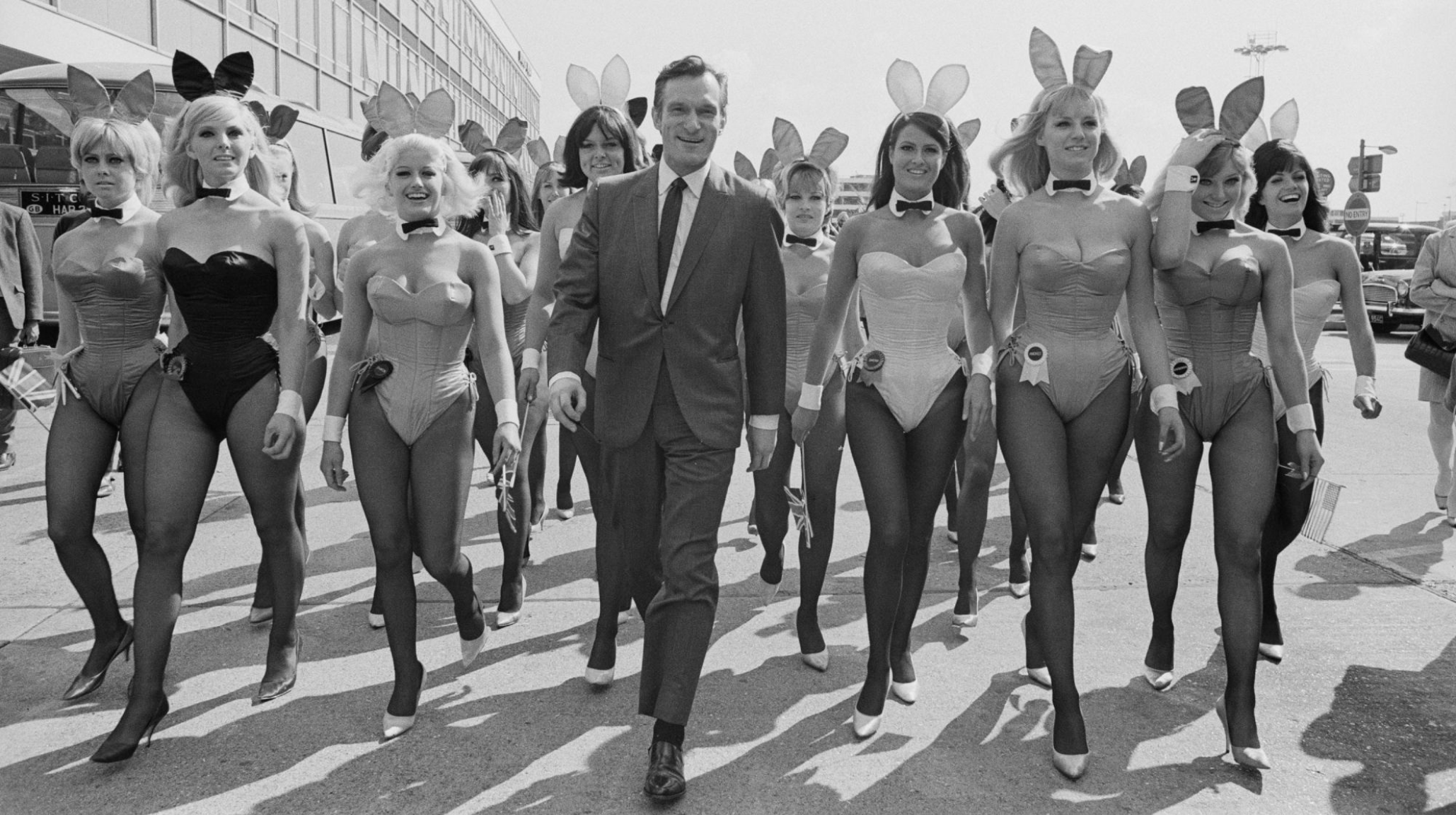

Throughout the years, Playboy has accumulated a complicated legacy around consent, sexual liberation, and countless allegations from women and staff against both Hugh Hefner and the company itself. In attempting to build his own mythology, Hefner irrevocably damaged the brand that bore his vision. For many, separating Hef from Playboy feels impossible—and perhaps it should. His idea of sexy dominated culture for nearly 50 years. He became the avatar of masculinity, if only to other men. From courting the most beautiful women to acquiring financial success to having proximity to fame, for men Hef was the blueprint.

But the internet was already democratizing attention. By the early 2010s, as Playboy's brand declined, suddenly any man with a microphone could position himself as the voice of masculinity. Alt-right rhetoric was picking up traction in the wake of 2016. Jake Paul, Ben Shapiro, Jordan Peterson, Andrew Tate, Joe Rogan, every guy with a podcast mic, they were already spreading online when Hef died a month before #MeToo, but his passing made the vacuum official. Without a secular figurehead of sexual liberation, young men turned elsewhere. President Donald Trump won 56 percent of men under 30 in November 2024, up from 41 percent four years earlier. At the same time, young men started leading America's religious resurgence, with Gen Z men closing the gender gap in church attendance for the first time while women leave organized religion.

Even the left swung conservative - in 2022, there was genuine discourse about banning kink and the leather community from Pride parades. The pendulum hasn't just swung back, it's swung toward a new puritanism.

The masculinity podcast bros sell is arguably worse than what Hef modeled. At least Hef advocated for gay rights, sexual liberation, and supported civil rights to some degree. These guys preach traditionalism, women are golddiggers, belong at home but shouldn't expect financial support. Men are the prize, if only to each other. And while Hef was far from perfect, Playboy did impact sexual liberation.

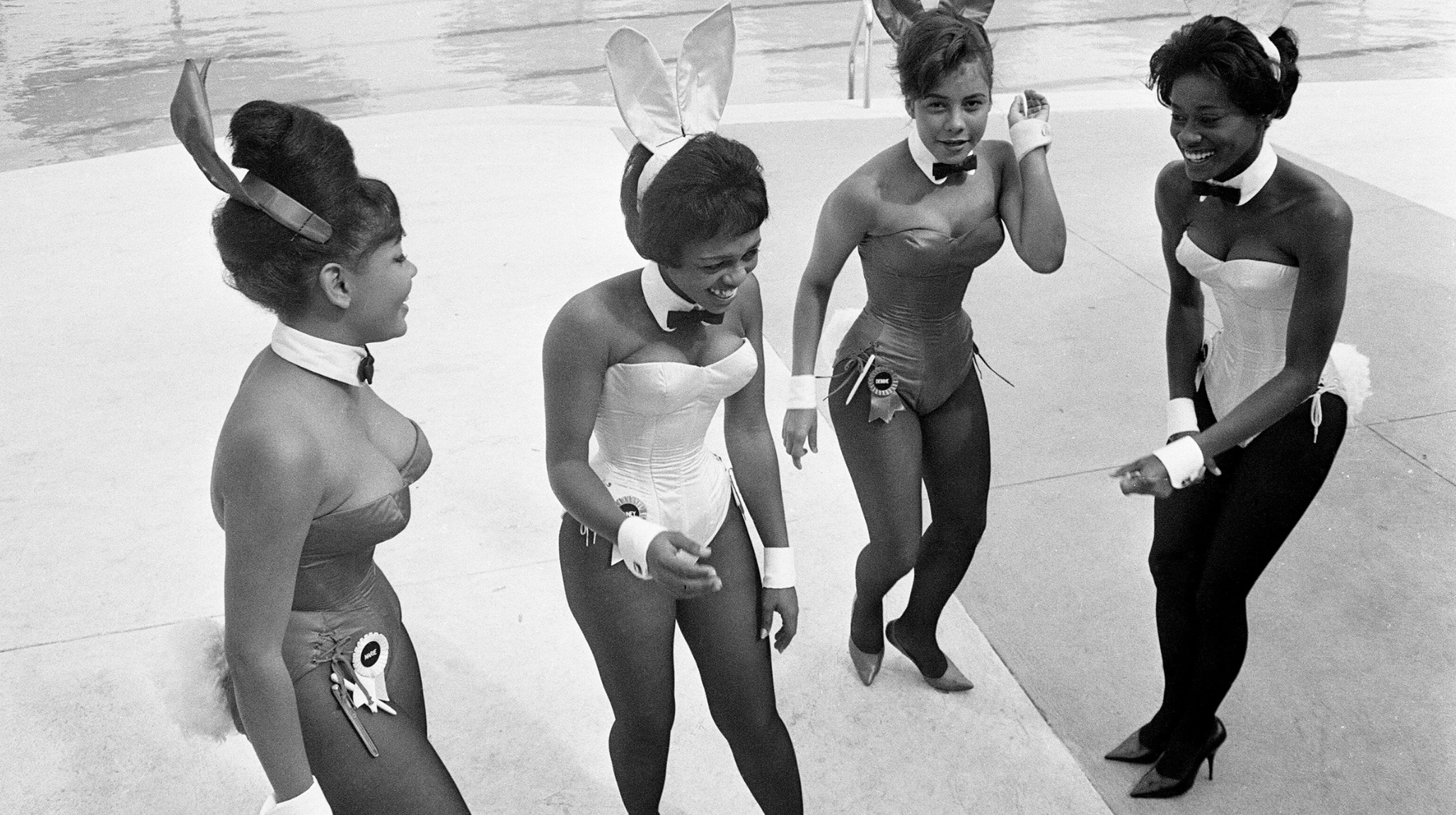

And while Hef was far from perfect, Playboy did impact sexual liberation. But here's what gets erased in every conversation about Hefner's empire: he didn't build it. Women did.

Zelda Wynn Valdes designed the bunny suit that became more iconic than the magazine itself. Marilyn Grabowski spent over 40 years as photo editor, but calling her an editor undersells what she actually did. Grabowski was injecting her own vision into every pictorial, shaping the art direction that separated Playboy from every other skin mag on the newsstand. That obsessive attention to lighting, composition, production value? That was her. It's why Playboy could charge more, why it sat on coffee tables instead of being hidden under mattresses, why it captured market share that competitors couldn't touch. You can spot Grabowski throughout The Girls Next Door if you know to look for her, working quietly in the background, even appearing in behind-the-scenes footage from Playboy's 1993 collaboration with Helmut Newton.

And beyond the creatives building the brand's aesthetic, women were the brand. Bunnies and Playmates weren't just decoration. Their personalities kept patrons coming back to the clubs. Their service, their charm, their ability to make men feel like they'd entered some exclusive world - that was what made Playboy special.

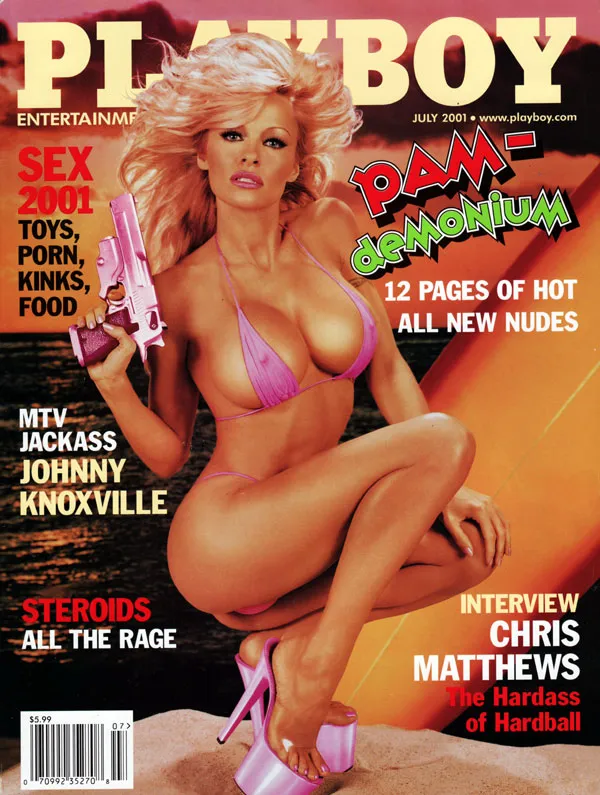

Women have continually reinvented the brand when it grew stale. In the 90s, Pam Anderson, Anna Nicole Smith, and Jenny McCarthy breathed life into a magazine that was losing relevance. In the 00s, Holly Madison, Bridget Marquardt, and Kendra Wilkinson did something even more radical: they brought in women as an audience. Young women who saw their personality, who watched The Girls Next Door and saw not objectification but relatability. Women have always made Playboy.

Which brings us to today. Playboy makes most of its money from licensing deals now, putting the bunny logo on everything from leather loafers to ashtrays. A reproduction of the signature bunny costume will set you back $181.Hefner sold the company to a private-equity firm in 2011. Last October, Cooper Hefner made a $100 million bid to reclaim his father's legacy. The board rejected it. Now the brand is run by Ben Kohn, Marc Crossman, Chris Riley. Executives, not auteurs or personalities. So, as an avid Playboy fan, I'm left wondering, where's the vision?

The pictorials that once defined the brand feel like afterthoughts now. When they feature internet celebrities, they're shot against plain backgrounds with no story being told, no world being built. The escapism that first drew me in has evaporated. Even when they invest in production value, something essential is missing. They don't seem to understand what desire looks like in 2025.

Playboy has a diversity problem, both in the models they cast and the desires they represent. Sports Illustrated is featuring plus-size founder Lauren Chan, disabled model Lauren Wasser, expanding who gets to be desirable. Meanwhile Playboy feels stuck in a heteronormative framework, showing the same narrow type of beauty, the same fantasy. But the problem goes deeper than just representation.

No one is telling us what's sexy anymore, which is objectively good and bad. Sexuality is everywhere now, accessible in ways Hefner couldn't have imagined. OnlyFans democratized erotic content. We have access to every kink, every fetish, every type of body and desire—but you have to search it out, find your creator, build your own fantasy. It's less "here it is" and more "go find it yourself." And no one is combining culture and sex in a way that's clicking in 2025. The magazine that once published Malcolm X, Jimmy Carter, Steve Jobs alongside centerfolds—that combination of intellectual and erotic—has vanished. Without that cultural conversation around sexuality, puritan culture creeps in.

They've tried celebrity creative directors and influencer columns, but it feels like they're keeping the lights on, waiting for someone to tell them what to be. What they need isn't celebrity partnerships. They need artistic vision.

The vision I'm fantasizing about would include queer people writing, modeling, photographing. Vocally and out. More sex workers who are unapologetic about it. Sexuality for women, not a male idea of what women's sexuality should be. When Playboy shoots cars, women are just draped over hoods. There's a way to shoot traditionally masculine things while honoring feminine beauty through set design, costuming, having women behind the lens. I do think they could straddle a lot of worlds with the right vision.

The magazine is returning to print in winter 2025. Millennials and Gen X still have deep attachment to Playboy, real nostalgia for what it represented. There's a way to play to that while modernizing, maintaining the fantasy but expanding whose fantasy matters.

I think about that kid in the basement watching Girls Next Door, looking for something to aspire to. The teen trying to learn about sex, and the young adult trying to understand her own sexual needs and desires. Now in my own thirties I'm faced with understanding my sexuality as I age. Playboy once combined sex with culture in a way that felt revolutionary. It could again. But only if it's willing to let women, all kinds of women, not just build the brand but define what it means.

The fantasy doesn't have to be about possession anymore. It could be about pleasure on your own terms. More importantly, it could fight this creeping puritanism by doing what Playboy did best—insisting that sex belongs in culture, not hidden from it. That intellectual and erotic aren't opposites but companions. That's the Playboy we need now.

In 2025, that fantasy feels more necessary than revolutionary. But revolutions have started with less.

Think I’m interesting? Subscribe to my email newsletter!