Last week, the Tea app—designed to help women safely share information about men they’re dating or considering dating—had a massive data breach. Days later, it had another.

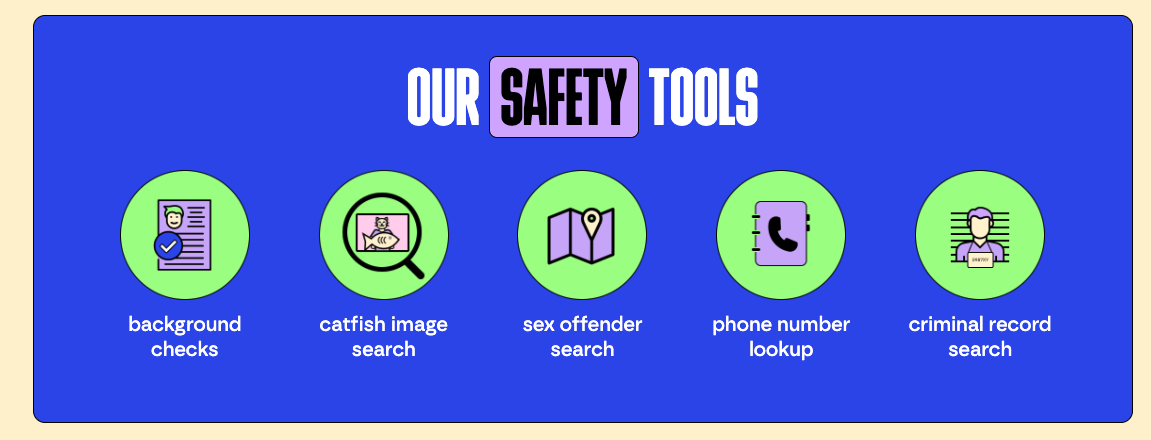

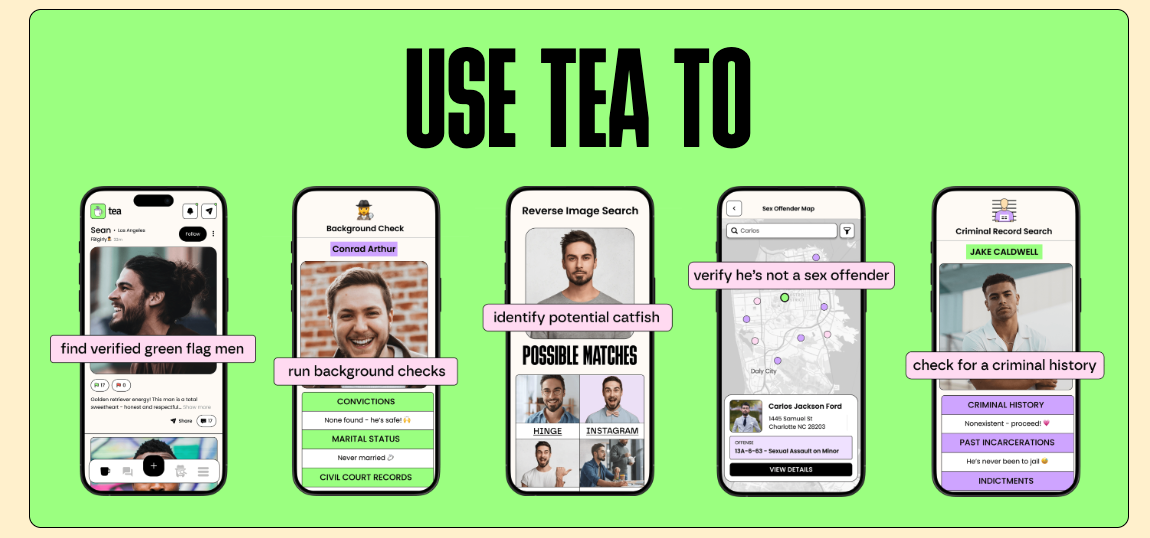

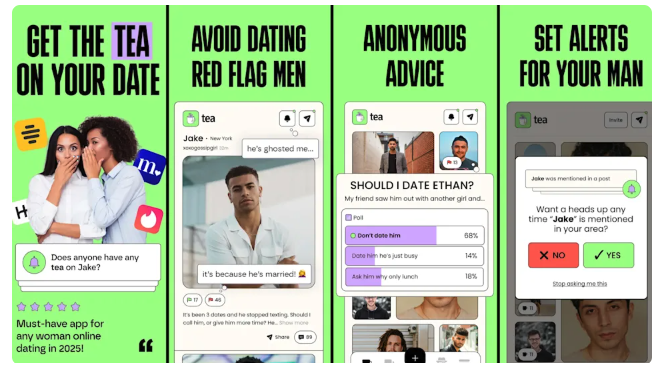

Marketed as a “dating safety tool that protects women,” Tea required users to upload selfies and, in some cases, government-issued IDs to verify their identity. In return, it promised a safer space to flag or vet potential matches—offering the option to run background checks, view user reports, and identify so-called “green flag” men. What users got instead was a full-blown privacy nightmare.

And the need for a platform like Tea isn’t abstract. Women are dating in a landscape where safety concerns feel increasingly valid—especially alongside a documented rise in conservative, anti-feminist views among Gen Z men. More young men are leaning into traditional gender roles, religious fundamentalism, and regressive politics, often shaped by internet culture. And they’re doing it in digital spaces that make it easy to obscure who you actually are. Tea promised to give women a tool to see through that.

According to reporting by 404 Media, the first breach was caused by an exposed Firebase storage bucket, leaking tens of thousands of selfies and driver’s license images. Tea issued a statement downplaying the severity, claiming the data was old and part of a “legacy” system. But that reassurance didn’t last. A second, more recent breach followed—this time involving private messages containing sensitive personal information: phone numbers, medical histories, even whether users had had abortions.

The fallout was immediate. Links to the leaked files were posted on 4chan. Someone even created a Google Map plotting user coordinates—no names, just pins and location data, scraped and published without consent.

Tea wasn’t just another dating app. Its entire brand hinged on safety—for women, by design. It failed at the one thing it claimed to do.

Amateur Hour Meets 4chan

The first breach stemmed from an exposed Firebase bucket—an unsecured cloud storage system often used in app development. In this case, it was what’s known as a legacy Firebase bucket: likely set up in Tea’s early days and left vulnerable. Think of it as an old, unlocked digital storage closet. If the right permissions aren’t configured, anyone on the internet can peek inside—or worse, download or delete what’s inside.

That’s exactly what happened.

At 6:44 AM PST on July 25, Tea identified unauthorized access to its systems. The exposed dataset included around 72,000 images—roughly 13,000 of which were selfies and photo IDs submitted by users for verification. The rest came from public-facing posts, comments, and messages.

Tea issued a statement saying the data came from “prior to February 2024” and was only retained for law enforcement reasons related to cyberbullying. In their public FAQ, they stressed that no email addresses or phone numbers had been accessed, that the photos couldn’t be linked to specific users, and that only people who signed up before February 2024 were impacted.

But after the leak went public, the fallout spread fast.

A user on 4chan—widely considered the worst site on the internet—posted a link to the files. Soon after, someone used metadata from the images to build a Google Map plotting user locations. There were no names attached, but it didn’t matter. An app marketed as a tool to protect women had quickly become a tool to expose them.

Then, just days later, a second leak emerged. Tea confirmed that private messages had also been accessed—despite earlier claims that no other systems were affected. Some of those messages included medical history, phone numbers, and information about whether someone had had an abortion. The platform temporarily disabled DMs and said it was working with the FBI and third-party security firms to investigate.

Researchers also found that the exposed infrastructure could allow someone to send a push notification to every user on the app.

These weren’t obscure backend bugs. This was negligence. Firebase bucket isn’t just a bad look. It’s the kind of amateur-hour engineering you might expect from a weekend project, not from a company boasting over a million users.

And when safety is your entire pitch—when your user base is built around fear, vulnerability, and the need for protection—this kind of failure isn’t just irresponsible or sloppy. It’s deeply unwell.

Red Flags and Long Nights

Tea positioned itself as a safety tool, not a dating app. The pitch was simple: give women a private, protective, secure space to share information about men, flag dangerous behavior, and identify so-called “verified green flag men.” It was marketed as built for women, with women’s safety at its core.

But underneath that promise, the infrastructure didn’t hold.

Verification on Tea wasn’t optional. Because the platform was women-only, users had to prove they were women just to get in. The app said that information would be securely processed and deleted right after approval. But as the breach made clear—nearly 13,000 selfies and IDs were still sitting in an unsecured Firebase bucket—those promises weren’t true.

Tea’s founder and primary funder, Sean Cook, is a former Director of Product Management at Salesforce. He’s said he built the app after his mother was catfished by a man with a criminal record. That origin story became the heart of the brand: a tool made out of concern, to fix something broken. But even with that mission in mind, the team didn’t build for the weight of what they were promising.

Big Verification, Small Locks

Tea’s failure isn’t just a one-off. It sits at the intersection of a much bigger problem: the rise of digital verification systems that demand more and more from users without clearly explaining what’s collected, how it’s stored, or who else can access it.

Tea required users to upload government IDs and facial images just to verify gender. That kind of barrier might make sense in theory. But in practice, it raises a whole set of new risks, especially when the systems behind it aren’t secure and when platforms rely on third-party vendors to manage storage and identity processing.

Most of the time, users aren’t told which vendors are being used. They’re not shown how long their data is stored, whether it’s encrypted, or how they can delete it themselves. Sometimes those details exist in buried Terms of Service. Sometimes they don’t exist at all.

Digital verification—especially for gendered or age-gated platforms—introduces the potential for long-term data exposure, algorithmic bias, and false flags. It creates new attack surfaces. And when data is stored longer than necessary, as it was with Tea, the consequences can escalate quickly.

At the same time, platforms love to throw around the word anonymous. Tea did too. It described itself as a “secure, anonymous platform” where women could speak freely. But real anonymity doesn’t exist when signing up requires a selfie and a government-issued ID. That’s not privacy—it’s exposure packaged as safety.

No Mods, No Net

Even before the breach, Tea operated in legally and ethically murky territory.

The platform allowed users to anonymously post about men—sometimes serious allegations, sometimes vague red flags. Some posts were tied to background checks, many were not. There was no clear editorial review, no visible moderation process, and it’s unclear how the app handled false claims or disputes.

That raises an uncomfortable question: where’s the line between protection and defamation?

Tea framed its model as harm reduction. Share your experience, protect someone else. In theory, that makes sense. But in practice, it opened the door to misinformation, character smearing, and reputational damage with no recourse. Users weren’t meaningfully guided on what was appropriate to post—or what legal risk they might be taking. And more importantly, there was no acknowledgment that what they shared could be traced back to them.

Tea described itself as anonymous, but online anonymity is conditional. IP addresses, metadata, and account behaviors leave trails. Users weren’t told how exposed they really were. And honestly, a lot of people don’t know how to protect themselves online in the first place. Basic internet hygiene—scrubbing EXIF data, masking IPs, thinking twice before uploading—isn’t common knowledge, even among people trying to stay safe.

Tea offered the feeling of security without explaining what that actually meant. It positioned itself as anonymous and protective, but those claims were vague and inconsistently enforced.

It gave users the intimacy of a safe space without the structure that makes one real.

Platforms like Tea are often trying to rebuild something that used to exist offline: whisper networks, group chats, friends, family, community members—the people you trusted to quietly warn you about someone. There were always ways to share information and stay safe, but they relied on actual relationships, not apps.

Tea tried to replicate that sense of protection without the responsibility. It mimicked community, but left its users exposed.

Move Fast, Break the People You Claim to Protect

The Tea app didn’t just leak data. It exposed how little most platforms are actually prepared to do when it comes to safety—especially when that safety is emotional, gendered, and high-stakes. Yes, there was a breach. But it wasn’t some sophisticated hack. It was the result of careless programming and even worse decisions.

It’s the logical endpoint of a tech culture still addicted to “move fast and break things”—even when what breaks is the very safety it claims to sell.

It’s easy to build something that looks like trust. Add a verification step. Promise discretion. Use the right words in your onboarding flow. But behind all that, someone still has to write secure code. Someone has to configure the database. Someone has to understand what safety actually means when your users are already navigating risk just by logging in.

Tea didn’t protect women. It asked them to hand over sensitive information in exchange for a false sense of security. And most people—through no fault of their own—believed it. Because we’ve been trained to trust that apps will handle the hard parts for us. And to be fair, why wouldn’t you? Surely checks and balances—like Apple’s app review process—would catch something if it weren’t safe. If it’s on the App Store, why wouldn’t it be secure? I don’t think the average person’s suspicion meter was set off. People assumed someone had done the work. Someone was watching the backend.

But a lot of the time, no one is.

Let’s be clear: Tea used intentionally misleading language in its marketing. It leaned into collective fear—particularly around the rise of conservatism and hostility toward women—and sold users a product full of promises it couldn’t keep. Words like secure and anonymous were everywhere, with little evidence they were ever true.

And while platforms absolutely need to do better, users aren’t off the hook either. We have to start taking our own data seriously. Practicing basic digital caution isn’t being paranoid—it’s just being realistic. Because no matter how much an app promises privacy, no one is guarding your information behind the scenes. If you don’t protect it, no one else will.

Tea won’t be the last app to fail like this. It’s just one that got caught.

Like what I have to say? Support me and subscribe to my newsletter.